In my last five years as a business coach, only two of my clients have had an operational budget in place when I started working with them. Let that sit for a moment—of my dozens of clients, most of whom run successful businesses that are turning profits, only a fraction of them had any idea how that profit was happening, or how to control it.

That’s all to say, if you don’t have an operational budget and are embarrassed to admit it, don’t be. You’re certainly not alone amongst small business owners. And my hunch is that the reasons you don’t have one are similar to those of my new clients. Maybe you:

- Haven’t made time to focus on budgeting.

- Think you aren’t savvy with numbers.

- Have money in your checking account. So why bother with a budget?

- Had a budget once and felt like it didn’t do anything for you.

- Are a little afraid of what you might find.

- See a budget as a constraint.

These may feel like powerful reasons, but let me call out the myth among them: An operational budget is not meant to be constraining or limiting to what you can do in your business. For most of us, budgeting means, “I need to cut back on costs and regulate my spending,” or, “If I have a budget then I can't buy anything.” But budgeting for business isn’t focused on limitation—it’s about vision and projection, about setting a financial goal and figuring out how to line up the numbers in your business so you can reach that goal.

Your operational budget is your profit plan. Simple as that. It’s a tool that helps you achieve your vision for the future. If you have a 35% profit goal for next year, you have two choices: Keep doing what you're doing and hope you hit that mark, or figure out what that 35% profit number is for your business and start looking at what your numbers need to be each month to get there.

Of the two, the latter is going to give you more control, and make you feel much more comfortable and confident about your business—even if the numbers terrify you in the beginning.

That fear holds many people back. That’s why creating an operational budget is a twofold practice: One part is building your skills and knowledge of the terms (which will demystify the budgeting process and make it less intimidating), and the other part is emotional. With my experience as a coach, I assure you that the emotional hurdle is the bigger one for business owners to overcome.

We all have an emotional relationship to money, and many of us avoid looking at the numbers at all costs. One client of mine was scared to death of making a budget, and without my push through that emotional fear, he probably would have stayed stressfully ignorant, wondering what was going on behind the curtain.

Like him, you may ignore the numbers because you feel like you need to be an accountant (you don’t), or are scared to face that they’re bad (they may be). But the truth is that while you can run a business with this mindset, you’ll never control it.

So, to help you create your profit plan (a.k.a. operational budget) for the 12 months ahead, I’ll cover the three steps to building and (most importantly) using it.

1. Understand the basic financial terms.

3. Work the data—and make it work for you.

1. Understand the basic financial terms

The key to getting comfortable with finance is to learn the basics, little by little. It peels away the formality of the matter and makes it all easier to manage. Let’s look at the financial terms of a budget plan and demystify what they really are.

Operational Budget

Simply put, an operational budget says, “Here’s our profit goal. Here’s what we’re going to spend and what we’re going to collect to get there.” Your budget is a forecast based on your historical numbers. It predicts and assumes the income and expenses that your business will generate in the future month, quarter or year. How? By looking at your income and expenses at this time last year. Understandably, making predictions based on the previous year may be a challenge if your business had to manage a crisis or experienced a lot of flux, particularly if you run a seasonal business. Try your best to make a close prediction based on the last couple months of the year. Just start somewhere.

Budget variance

Another term for this is “budget versus actual,” which says it all. Your budget variance report shows what you predicted for income and expenses for the period, and the actual numbers.

Say you own a sign-making company (like a current client of mine), and you predict that in January, you’re going to generate $10,000 in revenue and have a $5,000 payroll expenditure. At the end of January, your budget variance shows that you actually made $12,000 in revenue and spent $8,000 in payroll. Maybe this is a big surprise, but you’d likely know why. Having that variance gives you a real financial picture of that period, and helps you see and address any anomalies before they get out of hand.

Until you start comparing what's really happening to what you projected, you can't get better at projecting or adjusting to get more and more accurate with your budget predictions.

Budget cycle

Yes, a budget is cyclical (more on this later) and consists of four timing elements. Ideally you perform all four parts of the cycle, again and again, for as long as you have your business. Trust me, it gets more engaging as you go! The four parts are:

Budget horizon

This is the length of time you’re projecting for in your budget—most company budgets span one year. However, when you’re new to the budgeting process or to business in general, it’s perfectly acceptable to start with a three- or six-month budget horizon. As you have more historical data to work with, you can extend the budget horizon to a full 12 months. Looking at more potential economic instability in 2021, it’s a good idea to start with a budget horizon of only the first two quarters, as we’ve done at EMyth.

Review cycle

How often are you going to check back at your budget to see how it’s performing? Your answer is the frequency of your review cycle. Almost every business has a monthly cycle of budget review that coincides with its accounting cycle. A 30-day review is the golden number. It’s often enough to target small irregularities, but infrequent enough to allow natural patterns to develop in the numbers. Reviewing your budget daily, with the many micro-level ups and downs, might cause enough stress to give you an ulcer!

Planning cycle

How often are you going to update your budget? While the review cycle is about looking at numbers and variance, the planning cycle is about updating your goals and forecasts based on what you see happening. You may make some small adjustments during your monthly review to create more accurate forecasts for the next month, but major planning and budgeting happens annually, with quarterly reviews and forecast updates. Remember your budget is your profit plan, so your planning cycle is about making major changes to that plan—generally an annual activity. However, if you make changes to your strategic plans mid-year, you’ll also want to redo your budget to accommodate them.

Rolling budgets

You always want your budget to extend 12 months from today—which is why a rolling budget is valuable. As you complete your review of the current month’s numbers, you drop that month from the budget, then you add another month to the end of your budget year. So, after you reviewed January 2022, you should've removed that month, and added January 2023 to the end of the budget period. And what’s great is you already had the actual data from January 2022 to make your forecast for that new column. This way your budget always projects 12 months ahead rather than getting shorter as you approach your budgeting horizon. It’s simple enough to do, and keeping up with it saves you time in the long run.

Here’s an in-depth review of the process, with some great examples of fixed and variable expenses.

Now that you’re familiar with the financial terms of creating and using your operational budget, let’s look at where you find the data you need to get started.

2. Get the data you need

Now that you’re clear on the basic terminology, the next step is finding your data and getting it into order by creating your initial budget—the first of the two documents you need. If you’re like many business owners, this can be a big obstacle depending on how well you track your revenue and expenses. But before we dive into this step, it’s important to understand that your very first operating budget is a projection of a 12-month period. It’s your best estimation of what your numbers will look like based on historical data. It’s not going to be 100% accurate, but it’s the start of a work-in-progress.

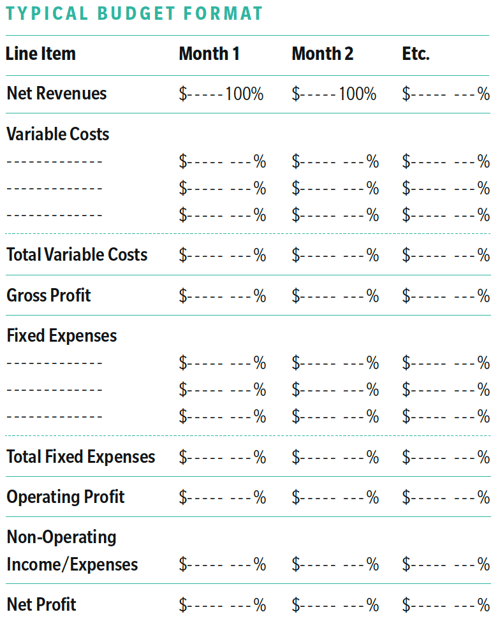

Here's a basic example of how to structure your document:

For you, beginning this step may be as general as breaking down expenses by a category, sourcing expense records or receipts, and asking:

What did I spend last year?

How can I find that information?

Does this figure represent a good estimate for what I might spend on this expense in the coming year?

For example, one of my clients was trying to calculate his spending on office supplies, but hadn’t ever really tracked that expense. He knew, though, that he’d bought all his office supplies from Staples using his credit card. “I got my credit card statements from the last three months and figured out that I’ve spent $1000 in this period,” he said. “So I’ll probably spend $4000 for the year in 2021.” With that beginning number in hand, he was able to make a reasonable guess at this particular expense—and repeat the process for other expenses.

But oftentimes, even that level of specificity can be a challenge. If you haven't kept good accounting records, you may only be able to say, “We had $500,000 in expenses last year, but we really don't know what that's all made up of.” If so, you have some options.

Stick with a sum total estimate

Take that $500,000 and project your best guess of what you’ll spend in the next 12 months. I don’t recommend this because it doesn’t set you up to start tracking moving forward. Even if you can’t separate the data now, it’s a good time to break this pattern and start getting real numbers to work with in the future.

Manually itemize expenses

Go line by line through whatever records you do have and begin separating out the expenses by category. Your accounting software may do this for you. Keep in mind that even if you do have categories or a chart of accounts, if you haven’t been the one deciding what goes into each category, the number may be incorrect. If that’s the case, start digging into who chose where to put things and ask yourself, “Should I continue doing it the same way in the future?”. This is how budgeting can start to positively impact your overall accounting and financial systems.

Refer to you profit and loss statement (P&L)

If you’ve tracked and segregated out expenses well, much of what you need to know to create your operating budget will show up in the last 12 months of both your profit and loss statement. If you haven’t (and many business owners don’t), now’s the time to start.

Talk with your accountant

Your accountant (if you have one) may be categorizing your expenses more than you think. Don’t go down the rabbit hole before checking in with them.

Tracking down all the numbers needed to build your first draft of an operating budget can be daunting, but the key is to start somewhere. Do the best you can with what you have at hand now, whether that’s a guesstimate or something more. While your first estimate is important, it’s not as critical as the review process later (more to come on that).

It may take up to a year before you can create an accurate operating budget. Until you’ve worked your first operating budget through a year-long cycle—replacing your guesses with actual numbers—it’ll be somewhat speculative. Next, we’ll look at how to refine your ability to make good projections.

3. Work the data—and make it work for you

This is where it can get tricky for many business owners—they have an operating budget in hand, but what then? Some think, “Alright, I made it. Now I'm going to set it down and never look at it again.” But that’s exactly what not to do if you want to turn your budget into a real profit plan. Your budget is a living document. You need to put it to work in a circular way by reviewing actual performance, comparing against the budget projections and adjusting accordingly.

Review monthly

Budgeting is not a once-a-year event. It's a frequent cycle of monitoring what's going on financially in your business, and questioning why a number is what it is. Ideally you’ll review your budget every month—often enough to take action on something that might be going wrong, but not so often that that data set is too small and produces a false read.

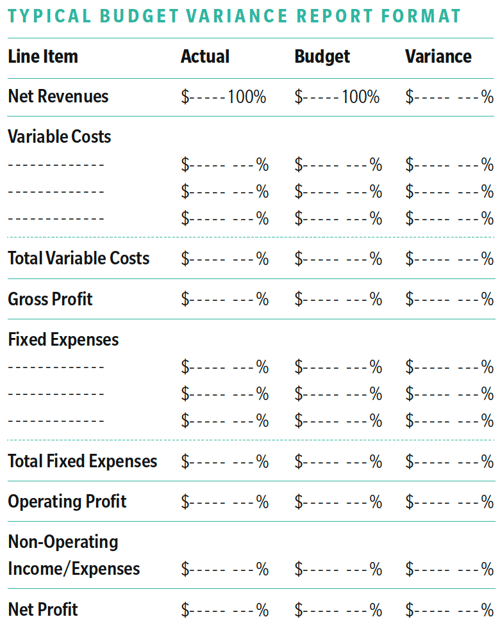

So, set a monthly appointment on your calendar to review your numbers and update your budget variance report, which is the second key document you need to produce.

Utilize a budget variance report

Your budget variance report shows your expected income and expenses next to your actual income and expenses, and the difference between the two. It also establishes your targeted profit margin and how close you get to that at the end of each month.

You may (very likely) discover that the numbers don’t match up in the beginning. That’s okay. Remember that this is a work in progress. If in your first month’s budget, you projected 50% net profit and you made 35%, that can be alarming. But there can be a variety of reasons why it doesn't match, and now you have all the revenue and expense numbers from that month to show you what those reasons may be.

Aside from helping to make accurate projections, this report will tell you when you should be concerned or when you should go get more information. For example, another client of mine who sells signs online recently saw his monthly revenue jump by 10%. And his cost of goods—what it takes him to produce the signs—also jumped, but by 30%. What the heck happened? Fortunately, he knew that the number was due to pre-ordering supplies in case of a continued uptick in orders. Whatever the case may have been, having those numbers in front of him signaled an important anomaly that he could’ve completely missed.

This tool makes you look at your business in a way you wouldn’t otherwise—and that’s the beauty of it. It makes you start to think about how the money connects to what's really going on week to week, month to month in your business.

Adjust to meet the needs of the moment

Let’s say you start your first budget in January and forecast $240,000 in revenue for the year—$20,000 per month. On your May report, you see that revenue is only tracking at $80,000 for the year instead of the $100,000 you forecasted. What happened—and what do you do now? Does your revenue peak and dip seasonally? Do you need to adjust all your numbers for the rest of the year, or is the revenue number actually on track?

Only you can answer these questions depending on the nature of your business and the specific details of what’s happened within those five months. Whatever the case, you now have real numbers and insight into how that’s going to impact your business for the rest of the year. And it may require you to revisit what you thought was going to happen and adjust for what’s really happening. Perhaps the most powerful part of all of this is that you’ll find yourself asking questions and digging for answers that you would have never looked for without your budgeting cycle and review.

The more you run through this cycle of reviewing, comparing and adjusting, the more comfortable you’ll be with your business finance—and the better you’ll be able to plan for profit. Seeing what's really happening financially in your business allows you to take action, constantly adjust and stay on track for a goal. When you get into that rhythm, you're running a business by the numbers. And after a year of tracking, you’ll be able to see that your business is bringing a net profit of 30% per year, and you now have the tools to forecast—and take action—to bring that up to 35%.

Comments